The Quad eyeing Indo-Pacific security

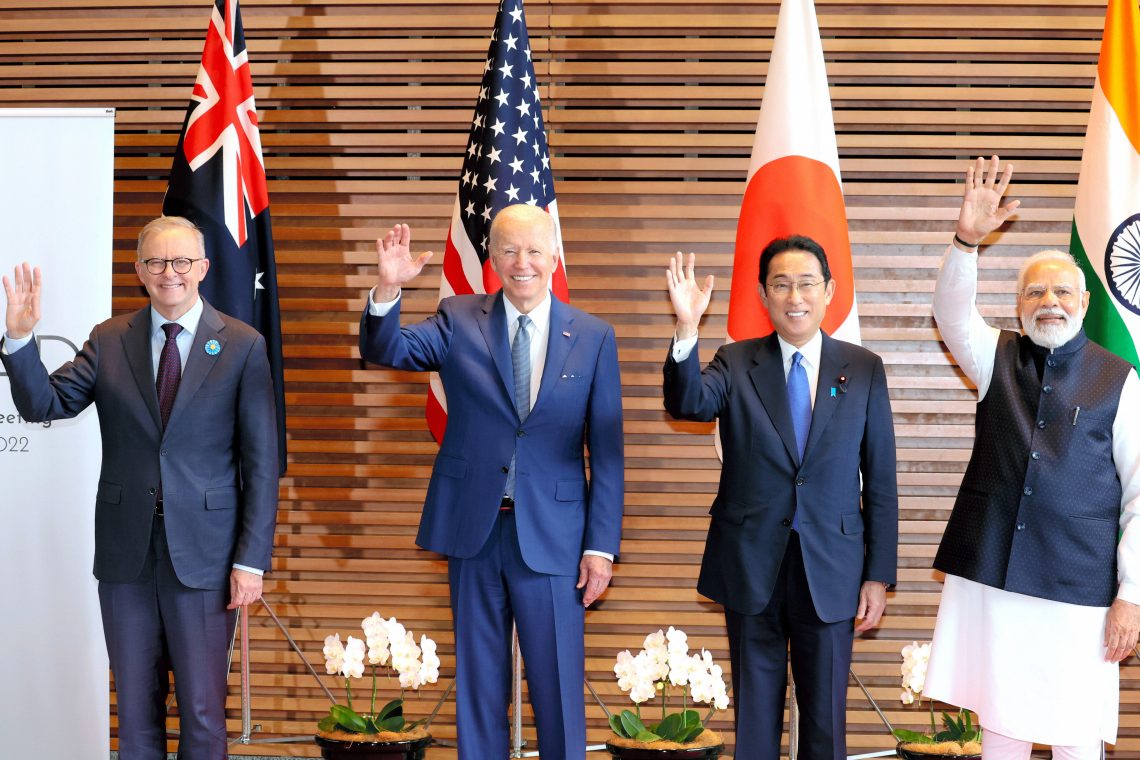

The Quad – Australia, India, Japan and the U.S. – is positioning itself to become the leading security body in the Indo-Pacific.

In a nutshell

- The group is to cooperate broadly but is unlikely to become a formal alliance like NATO

- All member countries benefit from coordinating security, diplomatic and economic relationships

- India’s role in the Quad could be complicated by New Delhi’s ties to Moscow

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, comprising Australia, Japan, India and the United States, has grown increasingly prominent in recent years. And while no one should expect the group, frequently referred to as the Quad, to evolve into a formal treaty alliance like NATO, it is set to become the preeminent cooperative security framework in the Indo-Pacific. In that role it will aim to promote peace and stability, bolster freedom of the commons (air, sea, space and cyberspace) and deter China.

U.S. commitment to the Quad will remain unquestioned moving forward, regardless of the outcome of the 2024 national elections in November. Both current President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, frontrunners in this year’s vote for America’s highest office, have vocally advocated for the framework.

The Quad’s slow start

The four nations, all of which prize their democratic institutions and adherence to the rule of law, initially came together to provide humanitarian support following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. After that, discussions continued and the first senior official meeting of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue occurred in 2007 on the sidelines of the annual Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting. But within twelve months, the initiative was moribund.

In subsequent years, several Track II initiatives (through unofficial contacts) continued to advocate for the concept, promoting it as a diplomatic means to address a range of the four countries’ common issues, from climate or global healthcare concerns to cyber and maritime security. The initiatives also facilitated joint coordination between the countries in an effort to mitigate the destabilizing influence of China in the Indo-Pacific.

Think tanks, including the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), the Vivekananda International Foundation, the Heritage Foundation and several Japanese research institutions have met annually to advance the Quad as a forum to expand security cooperation among the four countries and like-minded states in the region.

In 2016, prior to his inauguration, President-elect Trump revived the Quad concept. Additionally, key Asia experts joining his U.S. National Security Council (NSC) were advocates for the Quad.

Late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (who served in 2006-2007 and 2012-2020) articulated the concept of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” suggesting a framework in which nations could cooperate in promoting freedom of the commons without making it explicit that the purpose of this cooperation is to create an instrument to counter China.

In 2017, at Abe’s urging, the Quad resumed formal meetings, culminating in a conference of senior officials of the four nations. In March 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden and the prime ministers of the three other nations held their first-ever Leaders’ Meeting, virtually, followed by their first in-person meeting at the White House in September 2021. Various Quad meetings continue to take place and have expanded to include national agencies with diverse working groups and initiatives.

Facts & figures

The Quad timeline

- December 2004: In the aftermath of the earthquake off the coast of Sumatra and the tsunami disaster in the Indian Ocean, Japan, Australia, India and the U.S. form a group to lead the international relief effort

- May 2007: Quad officials hold a meeting for the first time

- November 2017: Senior officials start meeting regularly

- September 2019: Foreign ministers meet for the first time in New York

- March 2021: The first virtual Leaders’ Meeting takes place

- September 2021: The first in-person Leaders’ Meeting takes place in a format that continues.

Coming of age

In 2024, at the Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi, the Observer Research Foundation, ASPI, the East-West Institute and the Japan Institute for International Affairs, among others, participated in the first Quad Think Tank Conference.

The presence of senior officials from all four countries and their explicit endorsements of an expansion of the Quad framework bode well for its future. For example, Indian External Affairs Minister Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar asserted, “[T]he Quad is here to stay. The Quad is here to grow. The Quad is here to contribute.” Officials from Australia, Japan and the U.S. echoed him with similar remarks.

Grappling with geopolitics

Several key developments have led to the acceptance of the Quad, all of which are geopolitical factors that are unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

Japan’s foreign policy has become more explicitly anti-Chinese, with emphasis on the physical security of its territorial space and the defense of the commons linking Northeast Asia to the rest of the Indo-Pacific.

Current Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida advocates for the Quad, while Tokyo also seeks improved trilateral cooperation with the U.S. and South Korea and to more unambiguously address security cooperation with Taiwan.

Canberra now views China as a strategic rival and seeks security through partnerships – both formal and informal – with other powers, rather than having to balance relationships with China. Australia’s support of the Quad may have also helped it garner American favors, including Washington’s decision to share very closely guarded U.S. nuclear submarine technology.

For India, the Quad is an instrument for anchoring its bilateral relationship with the U.S. and countering expansionary Chinese activity in the Indo-Pacific. Both are fundamental to India’s diplomatic, security and economic strategies.

From a security perspective, New Delhi’s relationship with Washington delivers effective balance against China at both the strategic (nuclear deterrence) and conventional levels. Beijing, even with its additional investments in strategic and conventional forces, cannot fight a two-front war.

On the diplomatic field, a U.S. partnership adds weight to India’s geopolitical heft. As India strives to grow its economy, it needs the U.S. military presence to ease its defense spending burden. Also, being a strategic partner of the U.S. helps India attain better access to the lucrative U.S. market and thereby build its citizens’ affluence.

Beyond the evident value the Quad delivers to India on issues relating to economics and countering Chinese threats, New Delhi’s ties with Moscow bring some ambiguity to the grouping in a broader context. However, India’s access to the Russian military-industrial establishment may provide the Quad with unique perspectives.

Read more on cooperation among democracies

- AUKUS in perspective

- The U.S.-South Korea alliance navigates new political terrain

- Australia’s foreign policy pivot

As for the U.S., it benefits from the Quad principally because, until the emergence of the framework, Washington lacked any overarching instrument to manage its many security relationships in the Indo-Pacific. Most importantly, the U.S. is now party to a structure that oversees all the key lines of communication from Northeast Asia through the Indian Ocean, and stands to gain from intelligence sharing.

In addition, the Quad provides Washington with the possibility of new cooperative partnerships in a range of competitive arenas, including East Africa, where partners can cooperatively engage nations and provide an alternative to Chinese influence.

In all four countries, these developments have prospered with bipartisan and multiparty support at the national level and continue to be resilient even through leadership changes in Australia, Japan and the U.S. in recent years.

Rhetoric and action in the Quad

Since its formation, Quad members have portrayed the project as neither explicitly anti-Chinese nor primarily intended as a defense cooperation initiative against China. But some of the carefully worded readouts of Quad meetings suggest otherwise.

They have made clear that their strategic focus is the defense of shared interests, principally the freedom of the commons, rather than aggressively countering Chinese military power directly. The Quad is expanding cooperation in field technology development, particularly in cyberspace, space and maritime situational awareness.

In practice, all the Quad initiatives on protective and cooperative measures provide a foundation for making collective offensive military capabilities, as well diplomatic and economic instruments, more resilient. This is intentional and, in part, intended to serve as a deterrent against Chinese military adventurism in the region.

The Quad’s future

The nature of geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific, including aggressive Chinese counteractions, makes it unlikely that the Quad will evolve into a formal security treaty-based defense alliance against China. In part, this is because the region already has multiple flexible and adaptive frameworks for security and diplomacy, including a cascading array of trilateral and bilateral formats, treaty alliances and multinational organizations. By remaining relatively informal, the Quad can quietly achieve many of the functions performed by NATO, up to and including military contingency planning.

Debates over the Quad’s future center not on its role in security cooperation, which will continue to mature. Rather, there are differing views on how to operationalize the grouping. Calls range from desires for more formal institutional structures jointly managed by the four countries, the formal expansion of the Quad to include South Korea and the Philippines, or expansion into economic, climate and development cooperation, to others seeking to keep the grouping informal, flexible and nimble.

Scenarios

The Quad will certainly continue following elections in 2024, but how the format is utilized going forward depends on political priorities that will emerge from 2025 onward.

Most likely: China and India use the Quad to compete against each other

As the format becomes more strategically relevant, expect China to counter more aggressively. Beijing’s initiatives will not focus on trying to persuade Quad members to quit the group, but on discrediting the framework as alleged aggressors picking on China and exhibiting imperialistic tendencies. This narrative will target the Global South excluding India, which has first-hand experience dealing with China’s expansionary designs.

India, for its part, seeks to position itself as a leader in the Global South and among BRICS nations, and will compete with Chinese influence in this arena. The aim of remaining relevant in BRICS may also motivate New Delhi to maintain warm relations with Moscow.

Possible: The Quad becomes more NATO-like and aligned with the alliance

Expect more cooperation between the Quad and NATO countries. Joint military planning and exercises will continue while information and intelligence sharing and situational awareness are bound to expand. Closer operations between Quad nations and other like-minded states are materializing and are already evident in this year’s U.S. Navy-led Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) maritime exercises that are set to include not only all Quad members, but an additional 24 countries, making it the largest naval exercises ever, according to media reports.

The Quad will likely develop some institutional features in the fields of technology, intelligence, education and diplomacy. Expect more Quad activity to focus on East Africa and the Middle East, in addition to growing collaboration on island nations in Oceania and the Indian Ocean.

Possible: India’s role tenuous if Russia and China increase counter efforts

Finally, the Quad will, in the near term, increasingly be used as the forum for initiating, developing, debating and experimenting with new forms of cooperation for all the instruments of national power including cybersecurity.

This development will make counterintelligence and operational security a more important feature for the group because, without question, it will increasingly be a target for Chinese and Russian intelligence, cyber threats and disinformation. In this scenario, India’s role in the Quad will be tenuous so long as it continues to engage Russia as a peer.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.