Brazil heads for a Bolsonaro-Lula showdown

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is in a weak position ahead of elections in October. His most likely opponent is former President Lula da Silva, himself a highly controversial figure. These options offer little optimism for the country’s stability and investment climate. Could a “third-way” candidate gain traction?

In a nutshell

- President Bolsonaro is in a politically weak position

- Former President Lula is his likely opponent in coming elections

- Both politicians are likely to implement high levels of social spending

President Jair Bolsonaro is in his weakest position since taking office three years ago. His poor handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, increasingly brazen attacks on democratic institutions, and involvement in a series of public scandals have damaged his popularity less than 10 months before the October 2022 elections. Brazil’s dim economic situation has only worsened matters. The president’s chief rival, socialist former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, tied to the country’s massive Car Wash (Lava Jato) scandal and charged in corruption and kickback schemes himself, currently leads the president in the polls. Despite these deeply flawed options, no viable third-way candidate has emerged.

Response to Covid

As a previous GIS report detailed, President Bolsonaro’s response to Covid-19 has been disastrous. He downplayed or ignored the threat of the virus, turning Brazil into one of the world’s hotspots. Among other things, he discredited social distancing, rejected mask wearing, promoted superspreader events and spurned the vaccine, ignoring policy recommendations from his first two health ministers and then replacing them with more compliant ones. Predictably, Brazil has been devastated by Covid-19, which has officially claimed over 620,000 lives there.

In response, a Senate-led Commission of Parliamentary Inquiry (CPI) launched an investigation into the government’s poor response to the pandemic, citing accusations that President Bolsonaro and his government sabotaged isolation measures, threatened governors and mayors who applied restrictive measures, and refused to wear masks or encourage their use. The CPI’s main conclusion, released in October 2021, is that the Bolsonaro government deliberately sought to expose the Brazilian population to mass infection from Covid-19, and suggests that the president may have committed as many as nine different crimes. Regardless of whether the report’s findings may make their way to judicial authorities, the revelations will provide more ammunition for Mr. Bolsonaro’s opponents.

Institutional attacks

Mr. Bolsonaro has also faced political pushback from his ongoing attempts to weaken intragovernmental checks and increase the power of the executive branch. Facing the real possibility of an electoral rout next year – former President da Silva (popularly known as “Lula”), his presumed challenger, has a double-digit lead in the polls – the president has begun to cast doubt on the integrity of the electoral process. Without offering proof, he has repeatedly claimed that Brazil’s 2014 and 2018 elections had incurred instances of fraud and that the country’s electronic voting system is a sham. He even proposed a constitutional amendment to ensure voting systems included paper receipts, then threatened that he might not accept electoral defeat without a printed and auditable vote.

President Bolsonaro has begun to cast doubt on the integrity of the electoral process.

This has led to conflict with the other branches of government. He criticized Congress after the vote on his constitutional amendment proposal failed and has lashed out against the Supreme Federal Court after it approved opening an administrative inquiry into his “attacks” on the electoral system. The president has also publicly accused the court of politicization and abuse after facing multiple investigations: for alleged interference in the federal police, for dereliction of duty in relation to dubious contracts for the purchase of Covid-19 vaccines and for spreading misinformation.

More scandal

Although Mr. Bolsonaro rose to the presidency as someone untouched by the massive Car Wash corruption scandal that had implicated nearly the entire political class, he and his family have been beset by scandal. This has also hurt his political standing.

He was implicated in a scheme during his time as a federal deputy (1991-2019) in which he allegedly hired close associates as employees and then received a cut of their pay. Media reports indicate that the president transferred control of this arrangement, known as rachadinha, to his sons Flavio and Carlos.

The president also shut down the long-running Lava Jato investigation in February 2021, citing “no more corruption in the government” for the move. Brazilian society was rightly skeptical. Almost immediately afterward, a representative from the company Davati Medical Supply claimed that the Health Ministry’s logistics director, Roberto Ferreira Dias, had demanded a bribe of $1 per dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine in exchange for a government contract.

Weak economy

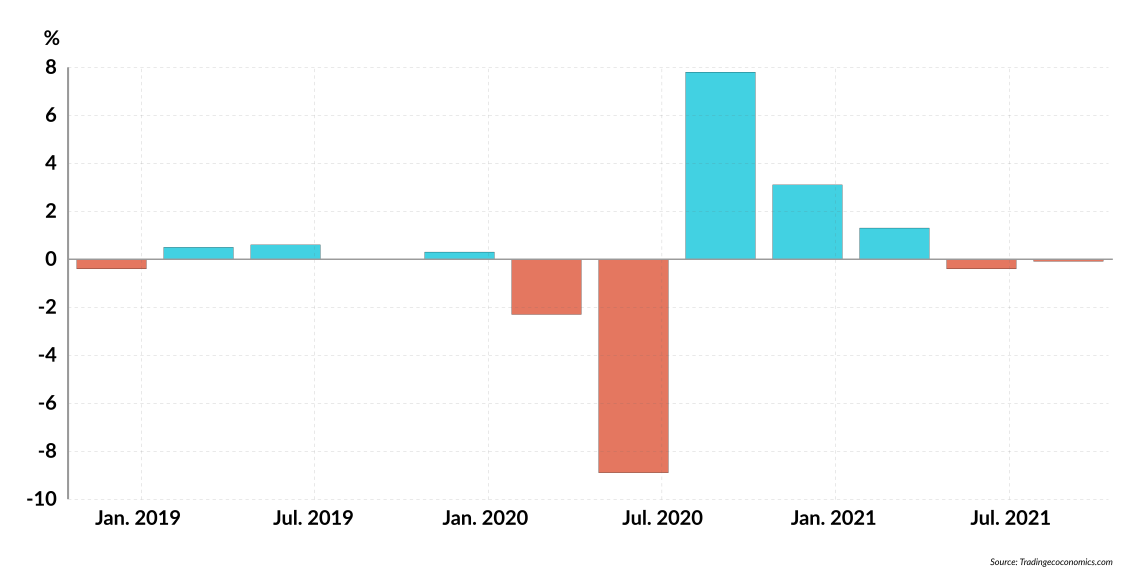

Perhaps what is hurting Mr. Bolsonaro’s image the most is economics. In early December, Brazil’s national statistics institute released figures showing that the country’s economy had entered a technical recession, after gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 0.1 percent in the third quarter, dragged down by drought, supply chain interruptions, and rising interest rates. Annual consumer inflation is running at a five-year high, despite extreme monetary tightening, and unemployment stands above 12 percent. The president’s narrative of being the pro-business candidate is a hard sell during a recession, when the economy is performing below pre-pandemic levels.

Facts & figures

Brazilian GDP growth (%), Q4 2018-Q3 2021

Mr. Bolsonaro, despite his conservatism on other issues, has responded by announcing a costly new social spending plan meant to aid his reelection prospects. This program, to be known as Help Brazil (Auxilio Brasil), will provide 16.9 million poor families with a monthly benefit of about $70. This seems to be a direct response to Lula’s massively popular social spending programs, which continue to benefit the ex-president in polls. Controversially, Auxilio Brasil breaches the country’s constitutionally mandated federal spending cap and contradicts the more traditionally orthodox preferences of the economists tied to the president.

The return of Lula?

Brazil’s presidential elections will take place in October, but for all intents and purposes, campaigning is already underway. Nearly all polls at this point suggest that the resurgent Lula would defeat the sitting president in a hypothetical runoff, with many giving him a double-digit advantage.

In many ways, this is surprising. Lula was released from prison in 2019 after being convicted of accepting renovations for an oceanfront apartment as a kickback from a construction firm – in addition to being charged in nearly a dozen other criminal cases involving alleged corruption and money laundering. He also presided over an era of prosperity that gave birth to the sprawling Car Wash scandal, which included kickback schemes involving some of the country’s most powerful politicians and largest companies, like state-owned oil giant Petrobras and the construction behemoth Odebrecht (now Novonor). Many projects under his administration were unsustainable, wasteful and tainted by corruption.

For many, the memories of an ascendant Brazil outweigh their reservations over the corruption that flourished under Lula.

At the same time, Lula left office at the end of 2010 with an astonishing 80 percent approval rating and is still beloved by many of the poor and those on the left. Under his watch, which coincided with a commodities boom, millions of Brazilians were lifted out of poverty, and Brazil briefly became a global player in the international system. For many, the memories of an ascendant Brazil outweigh their reservations over the corruption that flourished under his leadership, and which they see as endemic to Brazilian politics.

Scenarios

It is still too early to predict with great accuracy what will happen in the October elections. At this stage it appears to be a polarizing two-man race between the far-right President Bolsonaro and the socialist Lula, with controversial judge Sergio Moro acting as a possible spoiler. Regardless of who wins, the only guarantee is that Brazil will remain deeply divided.

Neither President Bolsonaro nor Lula would be likely to pursue unpopular measures of fiscal austerity, instead preferring to increase social spending. This will temporarily boost the approval ratings of whoever wins but bodes poorly for the country’s economic prospects. A lack of fiscal prudence may dim economic forecasts for 2022, muting GDP growth while exacerbating already high inflation and interest rates. In fact, it is now possible that Brazil’s economy will contract this year, after previous forecasts of a slight expansion. As it is, challenging external conditions, sharp monetary tightening and rising fiscal uncertainties suggest limited room for a meaningful rebound in the short term.

Lula wins the election

Given the circumstances described above, it is no wonder that President Bolsonaro faces long odds for reelection. Right now, despite his own defects, Lula is in the driver’s seat. Polls show the ex-president as the favorite to win and return to office for a record third term. This is the most likely outcome right now, with a narrow Lula victory leading to a potentially precarious situation (see below) and a double-digit victory making it more difficult for Mr. Bolsonaro to cast doubt on the electoral process and credibly claim fraud.

As president, Lula would likely pursue social spending and redistributive policies akin to those he previously carried out, although without the benefit of a commodities boom. It is unclear if he intends to move more toward the center, but his policies are much less sustainable under the country’s current fiscal conditions than under those of the early 2000s. He would also face fierce opposition from the same politicians that impeached his successor, Dilma Rousseff, in 2016 for improperly shifting public funds.

A Lula administration would require collaboration from other parties in Brazil’s fractured Congress. At the time of writing, Brazilian media reports that Lula has been negotiating with Sao Paulo state Governor Geraldo Alckmin of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) to agree to run as vice president. Whether or not this ends up happening, it is likely meant to send a signal to business sectors and other political parties. The center-right PSDB was one of the PT’s chief adversaries during Lula’s time in power, and a ticket with an establishment-friendly face like Governor Alckmin would be an important signal to markets.

Bolsonaro wins reelection against a fractured opposition

The second-most likely electoral outcome is that Mr. Bolsonaro manages to wield his economic power and benefit from a divided opposition to win reelection. The breadth of the anti-Bolsonaro opposition – from the far-left to the right – and its ideological heterogeneity work against it, as centrist parties and right-wing movements such as the Movimento Brasil Livre grudgingly endorse the president’s reelection or fail to coalesce behind either Mr. Bolsonaro or Lula. The likelihood of this increases as the leaders of Lula’s Partido dos Trabalhadores fail to take a strong stand or even denounce authoritarian takeovers in Nicaragua and Venezuela, scaring off more centrist voters.

If President Bolsonaro wins reelection, Brazil can also expect more of what it has seen the past three years: controversy, polarization and institutional headbutting, with populist economics and continued erosion of democratic institutions. Mr. Bolsonaro’s institutional attacks will likely escalate, while key elements of the president’s governing coalition defect.

A four-year term is not guaranteed, especially if the president is unable to court new allies. This would be neither unexpected nor unprecedented. There are currently more than 130 impeachment petitions against President Bolsonaro in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies and over half of the respondents favored such a move in a September Datafolha poll. Moreover, two of Brazil’s previous four elected presidents (Fernando Collor de Mello in 1992 and Dilma Rousseff in 2016) were removed via this process. President Bolsonaro continues to alienate politicians on both the left and the right, and a particularly egregious challenge to the country’s institutions may unite the two sides against him.

A third-way candidate emerges victorious

The least probable outcome, at least at this stage in the electoral process, is for a third-way candidate to emerge from the center to capture moderate voters dissatisfied with their two extreme options. One potential spoiler is Sergio Moro, the controversial Lava Jato judge and the Bolsonaro administration’s justice minister who formally entered politics in November by affiliating himself with the right-wing Podemos party. However, the former judge’s negative ratings exceed 60 percent, second only to the divisive president, which augurs poorly for his chances.

If he were to win, Mr. Moro is the candidate most likely to pursue an orthodox economic policy that would please investors and business leaders. However, as an outsider politician who was a key figure in convicting politicians, he might find it difficult to build legislative coalitions, especially with the left.

Bolsonaro loses, claims electoral fraud, and refuses to accept defeat

It is also plausible that President Bolsonaro refuses to leave office after defeat at the ballot box. Given the president’s willingness to cast doubt on the country’s electoral system this long before the election, it seems almost certain that he would react to any electoral loss much like former U.S. President Donald Trump – claiming fraud and failing to concede. In this situation, there are real concerns among analysts that the president may attempt to hold onto power through nondemocratic means. His attacks on the country’s voting system and government institutions, as well as his ties to the military and national police, suggest that, at the very least, he will not be willing to go down without a fight. This would obviously be the worst scenario for Brazil’s stability, institutions and investment climate.