The financial elephant in the room

Like medieval alchemy that failed to turn lead into gold, today’s easy-money policy of central banks and governments will lead to crisis, not economic growth and prosperity. Neither politicians nor bankers seem capable of returning to responsible policies.

In a nutshell

- Government policies of incurring high deficits appear to be based on a belief in alchemy

- Easy-money policies of central banks allow governments to continue irresponsible spending

- Such practices violate sound banking rules and may lead to a financial crisis of epic proportions

- Banks and governments seem addicted to this dangerous system and incapable of ending it

- Inventions such as cryptocurrencies, maligned by many bankers and politicians, may be the key to a solution

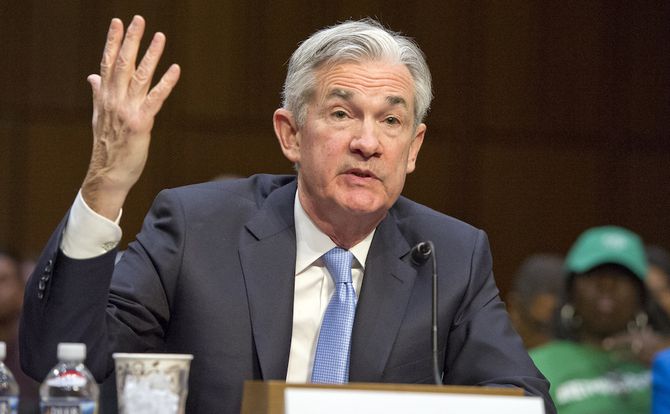

Three compelling messages on the economy have come through over the past few days. First, neither the United States Federal Reserve nor the European Central Bank (ECB) have imminent plans to end their easy-money policies. Second, the Italian government is considering paying off its arrears to suppliers with new small-denomination bonds instead of euros; the receiving parties would be able to pay with these instruments in Italy. And third, Facebook announced the creation of a new cryptocurrency, the libra, that it hopes will be accepted as a form of payment – one of the critical functions of money. The company issuing the currency, Libra Networks, was registered on May 2, 2019, in Geneva.

One might question the need for cryptocurrencies, as there is an established monetary system in existence – in theory, guaranteed by central banks as institutions of public trust. To resolve this doubt, you may want to take a look at the last 20 years of monetary policy.

Debasing the system

Following the financial crisis of 2007-2008, Mervyn King, the former governor of the Bank of England (2003-2013), wrote a book entitled The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy(2016). In it, he accurately described how the neglect of sound monetary and banking practices by governments, central banks and the financial sector – this neglect being a consequence of the wrong incentives created by cheap money – had led the world into the dangerous crisis.

Eight years after the onset of the financial crisis, such thinking still persisted.

Encyclopedia Britannica defines alchemy as a form of speculative thought that, among other aims, tried to transform base metals such as lead or copper into silver or gold, or to discover cures for disease and ways of extending life. Alchemy was a discipline that fascinated many in the late medieval and the Renaissance era. Mervin King was right to use the word to describe the government policy of incurring high deficits. It is based on the belief that these deficits can be financed, and the economy enhanced, through increasing debt and issuing cheap money.

Monetary policy has been used to grow the economy in the violation of any sound monetary practice. These wrong incentives led to an economic expansion driven mainly by public and private consumption, financed by debt, not income.

Unfortunately, when Mr. King published his book, eight years after the onset of the financial crisis, such thinking still persisted. If anything, the alchemy hype became even stronger. The Fed, along with the ECB and other central banks, did not just cut interest rates close to zero or even negative territory. They also allowed governments to keep on piling up debt with large-scale purchases of government bonds. In Europe, the markets were further flooded with money by the ECB’s bond-buying program, which also included corporate bonds.

This monetary hocus-pocus punishes savers, destroys pension funds and inflates asset bubbles, especially in real estate and equities. It also allows governments to continue their irresponsible fiscal policies. The result is an economy financed to the detriment of future generations. The puzzling fact is that many of the most renowned economists, such as Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz and Kenneth Rogoff, also support this crazy deficit spending doctrine, while neglecting its catastrophic long-term consequences.

Incapable of repair

At the turn of 2017 and 2018, the central banks in Washington and Frankfurt announced that they would end, or significantly scale down, their bond-purchasing programs, and eventually restore higher interest rates. The claim was that expansive monetary policies had been successful, and that the general economy had improved. That was not the case, and the Fed, as well as the ECB, have since announced a return to expansionary monetary policies. The alchemy continues.

Sound monetary policies demand that central banks ensure the provision of adequate liquidity to the economy and safeguard the currency’s purchasing power. Their engagement in fiscal or economic policies must be avoided. In consequence, central banks ought to be independent of government to make sure that short-term politics does not influence the creation of money.

What we are now witnessing, however, is an even worse situation. Central banks are not just being guided by politics, but through their no-interest policy and bond purchasing, they are directly engaged in fiscal and economic policymaking.

Now we are seeing signals that central banks are unable or unwilling to return to sound monetary policies and the protection of currencies’ value. This raises very legitimate cause for concern.

Regulatory requirements range from very complex to unmanageable.

A lot of money has been artificially created in recent years. These funds, however, have not resulted in sufficient investment in the economy. This has become a sore point among economists. Increasingly complicated mechanisms are being devised to protect the financial system, especially banks, from risks. Prudence is a primary duty of bankers, but exaggerated risk aversion leads to stagnation. Have we reached this stage? Whatever the case, regulatory requirements on the supranational, national and institutional levels now range from very complex to completely unmanageable.

This complexity creates another difficulty: banking services, especially in retail and smaller operations, are becoming very costly. This is mainly a problem of cross-border transactions, which are very common in Europe and most emerging markets, but less frequent in the U.S.

Overall, the current monetary policy does not inspire confidence in the traditional financial system. It will also not be able to solve the debt crisis.

Hopeful inventions

Italian officials are rightfully concerned about the government’s debt and the solvency of the country’s banking sector. Apparently, they want to avoid the agony of Greece, which has labored to avoid a sovereign default and maintain the common currency. But the Greek saga shows this is not the way to go. A more realistic approach could be to issue tradeable promissory notes in exchange for government obligations. These instruments could eventually become a new currency.

Tragically, the great project of the euro has been jeopardized by the irresponsible policies of nearly all member countries (with the possible exception of Luxembourg). It is regrettable that, in the process, the banking system has been weakened and become less competitive. When regulations and lethargy block innovation, the retail customer faces exaggerated costs.

The belated response of central bankers and the stubborn refusal of top economists to worry about the staggering debt indicate helplessness. A crisis endangering the global economy and social cohesion (as private savings and pension money are at risk) can be delayed, but continuing on the current path will only make it worse.

The rise of cryptocurrencies challenges the traditional monetary system. Yet it has not spurred a realization among central bankers and legislators that the old system needs drastic reforms and regulatory streamlining. To the contrary, the main reaction has been repeated attempts to vilify cryptocurrencies.

All new technologies have teething troubles, but marginalization is not the answer. The Italian government has at least recognized the fiscal and the currency elephant in the room. Its solution, however, does not get to the root of the problem – the oversized public sector and overspending.