India has limited ability to feed a hungry world

Government subsidies and inadequate investment have led to low agricultural productivity, often leaving India with harvests that can do little more than meet domestic food demand.

In a nutshell

- Many factors have curtailed India’s ambitions to be a top food exporter

- Restrictions on rice exports may follow the curbs on wheat sales abroad

- Eventually, India needs to inject market forces into its agricultural economy

Considered a possible replacement for Ukrainian wheat supplies, India banned exports in May after a heatwave reduced its harvest, underscoring the limits of the nation’s agricultural industry in alleviating global food shortages. The country has since allowed a few million tons of wheat exports, but the present monsoon will determine whether a ban on rice exports will follow.

India thought it could boost its international profile while earning additional revenue when it tried to compensate for an expected drop in Ukrainian and Russian wheat exports. A combination of weather and inflationary pressure forced India to scale back these ambitions, a reminder of the thin agricultural production margins within which even a large low-income country operates.

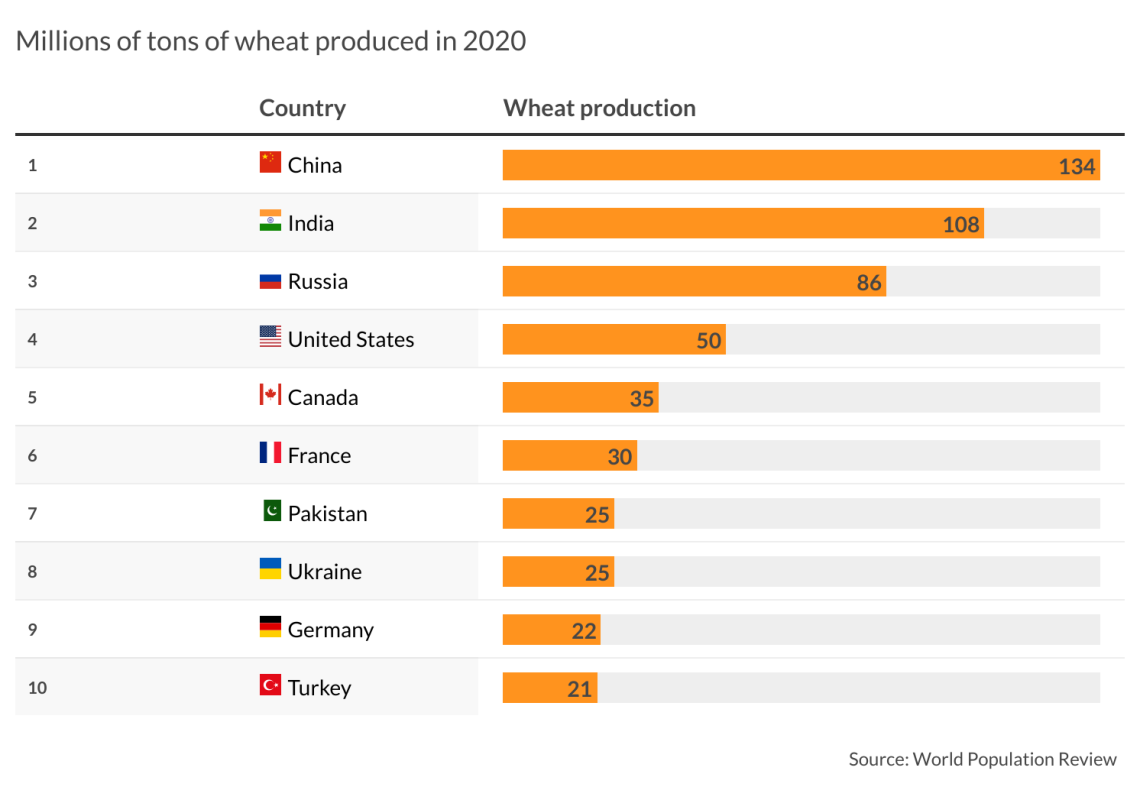

Concerns about war-disrupted wheat supplies from Ukraine and Russia led global prices to rise from March. At about the same time, early projections said India was heading for a record 110 million-ton winter wheat harvest, 10 percent above annual domestic consumption needs. With an additional 20 million tons in stock, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi was confident it could export $5 billion worth of wheat. During a virtual meeting with the Indian diaspora in Germany in early May, Mr. Modi said, “At a time when the world is facing a shortage of wheat, the farmers of India have stepped forward to feed the world.”

Facts & figures

Wheat harvest disappoints

Even as he spoke, however, the reality was shifting. A heatwave in northern India drove temperatures to 45 degrees Celsius, shriveling the grain standing in the field and reducing the crop by 10 to 11 million tons. Expecting lucrative export orders, traders had begun buying directly from farmers and drove up high domestic prices. By April, domestic wheat prices were 19 percent higher, year on year, with some regions recording increases of 33 percent. Lines remained crossed between the agricultural and commerce ministries and things came to a head in May. While Indian officials were overseas signing export contracts, a group of ministers was briefed on how food prices were heading for politically dangerous territory. On May 13, the government announced an immediate ban on all commercial wheat exports. Only government-to-government sales would be allowed, and that on a case-by-case basis. New Delhi also cited evidence that speculators were picking up wheat and hoarding supplies.

Related report by Pramit Pal Chaudhuri

Modi pulls back on agrarian reforms

Limits on India’s ability to export

Though India’s wheat exports are only a fraction of the quantities traded by Ukraine and Russia, the ban was the latest in a series of trade restrictions announced by various inflation-spooked governments. The ban led to Chicago grain futures rising 4 percent. Several governments criticized India, but for New Delhi, all that mattered was that domestic wheat prices fell 6 to 7 percent.

Under World Trade Organization rules, India is banned from exporting grain produced through subsidized inputs like fertilizer and power.

However, India quietly reassured some economically distressed countries of continued supplies. Bangladesh, which bought nearly half of India’s 7 million tons of wheat exports last fiscal year, was told it had nothing to worry about. Food aid commitments to Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar remained untouched. By June’s end, India had also promised wheat shipments to the United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Oman and Indonesia.

The Indian government has not touched its wheat stocks. This was partly because the Modi government is using several million tons for a rationing program to help poor Indians affected by two years of Covid lockdown (the program is to run until September 2022). Another reason is that under WTO rules, India is banned from exporting grain produced through subsidized inputs like fertilizer and power. New Delhi argued for the rule to be relaxed, but it ran into opposition from developed countries at the WTO.

Facts & figures

Government stocks are considerable: 31 million tons of wheat, 33 million tons of rice and 25 million tons of other grain. Yet further export restrictions are being debated, this time for rice. The Modi government is watching the monsoon, presently working its way across India, as that will determine the size of the autumn harvest, which is primarily rice. India is the world’s largest rice exporter. Weather uncertainty, the possibility of extending food doles, supplies for friendly neighboring countries and a need for stocks to hold down domestic prices – are all considerations as New Delhi wonders how much is enough.

Scenarios

The most likely path in the coming months is conservative management of domestic grain markets, with exports allowed in dribs and drabs. India had already exported 1.5 million tons of wheat before the May ban and a further 1.8 million tons in the six weeks that followed. If the coming harvest is in the normal range of expected agricultural production, New Delhi may feel confident enough to release a few more million tons. This would take India’s exports close to last year’s levels. Rice export restrictions, potentially the most damaging to global food prices, are unlikely. Existing stocks are large, and the monsoon has already covered most of the east and south rice-growing regions. All of this would imply that most export restrictions are being lifted by September or October so long as overall inflation does not spike.

A worst-case scenario would follow a monsoon failure and slower economic growth. At this point, a ban on the commercial export of rice would be very likely, as well as further restrictions on wheat. The government would have to run down its existing stocks to hold down prices and provide for ration schemes that could be extended till the end of the year. India is not a significant wheat exporter, but it is crucial to rice markets, and an export ban would drive up global prices. Presumably, all of this would also feed into a worldwide momentum toward agricultural protectionism with all the concomitant problems that would cause.

A positive impact of this entire episode would be if it inspired a long-term policy response. Namely, encouraging the Modi government to make another attempt at injecting market forces into India’s agricultural economy. An earlier reform attempt had to be withdrawn following widespread protest by farmers who were beneficiaries of the existing subsidy structure. India’s on-and-off policy response to farm exports is a vicious cycle. As farmers lack the resources to invest in higher productivity, India’s farm sector generates just enough produce for domestic demand. The best way for farmers to raise their game would be to export, earn enough to invest in technology and infrastructure, and boost India’s absurdly low agricultural productivity levels. The result would be India becoming a genuine and dependable player in the global farm trade.