Europe’s ‘historic’ deal and the future of the EU

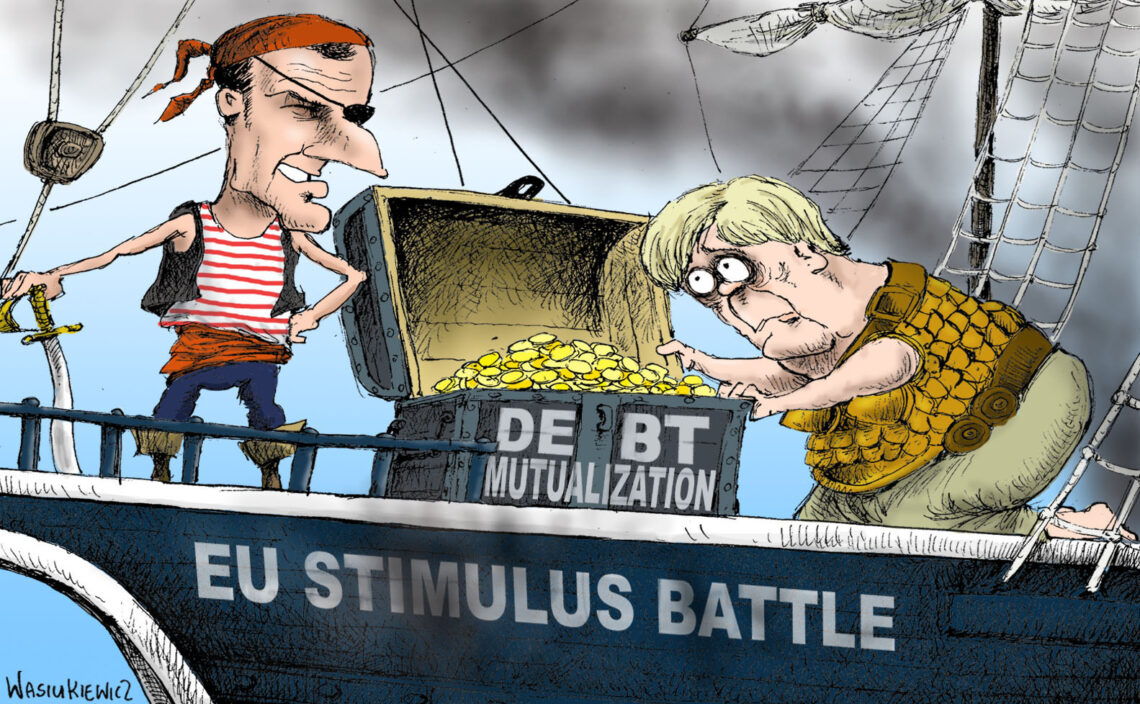

Many have hailed the EU’s July decision to partially introduce debt mutualization as a “historic step.” Massive as it is, the stimulus package is unlikely to fix Europe’s fragile and crisis-stricken economies, even if the Union’s show of unity has firmed it politically.

In a nutshell

- The EU’s debt mutualization policies are meant to be limited, exceptional measures

- Europe’s spendthrift southern countries see them as a harbinger of things to come

- The frugal northern countries may join forces to influence the EU’s further evolution

The European nations’ agreement on a bloc-wide recovery fund, which emerged from the European Council between July 17 and 21, enables a partial mutualization of newly-issued European debt.

The European Union member states will be able to collectively pool debt obligations of up to 750 billion euros, out of which 360 billion euros will be allocated in loans and 390 billion euros in subsidies. Many among the media and several politicians have hailed debt mutualization as a “historic step” (as per EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen) thanks to the “magic of the European project” (Council President Charles Michel).

Facts & figures

The nuts and bolts of the EU’s stimulus package

On July 21, the 27 European Union member states unanimously agreed to a stimulus package to combat the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The long-term Multinational Financial Framework (MFF) defines the terms and conditions for a debt mutualization under the 750 billion euros ($857 billion) Next Generation EU (NGEU) program. At a special meeting of the European Council, state leaders affirmed their commitment to solutions that would integrate the interests of all member states and be “significant, focused and limited in time.”

- The most attention-drawing feature of the NGEU is the provision that authorizes the European Commission to borrow funds on behalf of the Union

- The plan calls for raising 750 billion euros on the capital markets, with new net borrowing to stop by the end of 2026

- The raised funds are to be used to provide 360 billion euros in low-cost loans and 390 billion euros in grants to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, without regard for member states’ preexisting economic conditions or commitments

- The repayment of debts by the Union will be scheduled to ensure “steady and predictable reduction in liabilities” until 2058

- Principal repayments due to the Union in a specified year will not exceed 7.5% of the maximum 390 billion euros allocated for expenditure

- State leaders also agreed on a temporary increase in their public debt ceilings by 0.6 percentage points to ‘create sufficient budgetary space’

- As member states are not expected to ramp up their contributions to the Union’s budget, the Commission plans to levy new environmental and digital taxes to help defray the expenses

- The Commission is yet to release specific country-by-country allocations, it decided on a series of stipulations that will help guide the future disbursements that are expected to begin in 2021

- The Commission reserves, as a last resort, the right to ‘call more resources’ from member states as it deems necessary, without increasing the ultimate liabilities of the collective

- Member states will be able to access 672.5 billion euros through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). It is hoped that 70% of grants will be committed in 2021 and 2022, and the remaining 30% by the end of 2023

- The maximum volume of the loans for each member state is not to exceed 6.8% of its gross national income (GNI)

- Prefinancing for the RRF will be paid in 2021 and should amount to 10%

- Member states are required to prepare national Recovery and Resilience plans for 2021-23; the Commission will then assess the schemes for consistency with country-specific conditions, including strategies for strengthening green and digital economies

- Upon the Commission’s proposal, countries will need to obtain approval from the European Council by qualified majority. Payment requests will be contingent upon meeting the strategic goals, which will be reviewed and adapted in 2022 to determine final allocations for 2023

- Member states may request that the President of the European Council refer matters of other states’ ‘serious deviations from the satisfactory fulfillment of relevant milestones and targets’ to the next European Council. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte is credited for the inclusion of the oversight mechanism.

Source: the EU, Yale University

Hamiltonian moment

After two months of bargaining, the scheme that has emerged is described as a materialization of Europe’s “Hamiltonian moment.” Indeed, the historical parallel invokes some of the challenges faced by the EU. In 1790, United States Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, was able to convince the 13 American colonies to collect their public borrowing and initiate debt mutualization. At the time, the U.S. had only recently become a federation, after being a confederation until 1789; Virginia was then the “frugal” state reluctant to join the deal, just as Germany and a handful of Northern states had been for quite some time in today’s EU.

The recovery fund will probably not do so much to help Europe’s fragile economies.

After years of resisting debt mutualization projects coming from “Southern” countries like Italy or France, Germany at first gradually, then rapidly gave way in May 2020. In the post-Brexit context, the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic could potentially disrupt the EU. “Exceptional events call for exceptional new methods,” stated the German chancellor after the deal.

The recovery fund will probably not do so much to help Europe’s fragile economies recover. However, the Union’s demonstrated ability to build consensus, make concessions against concessions, and to show unity may all matter more – especially because Germany took over the six-month Council presidency on July 1, 2020.

The creation of debt mutualization at the European level is seen by many as a new step in the EU’s construction process, opening the door to federalism. To go back to the narrative of a Hamiltonian moment, the differences between the two vents are significant, in any case. Secretary Hamilton converted the confederated states’ legacy debt from the war of independence into a national debt. In the current European deal, there is no mutualization of existing debt and new liability will be limited.

However, changes are already being prepared on the fiscal front. To partially repay the loans, new European “own resources” will be levied, such as a tax on nonrecyclable plastic, starting from January 2021, and on digital services. A “carbon adjustment mechanism” at the EU borders is to be implemented by January 1, 2023; whatever the terminology, it means a tax. A financial transaction tax is also possible.

Centrifugal forces

In reality, some of these new “own resources” will not be easy to acquire legally and effectively. Digital taxes not only reek of protectionism but, aimed clearly against GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft), also of anti-Americanism. The carbon tax is complicated to calculate, given the uncertainty of the amount of carbon dioxide in a given product. Such measures are prone to leading to trade conflicts. Moreover, while the digital levy can clash with the EU’s vaunted goal of increased digitalization, the financial transaction tax could prove self-destructive for the European sector.

The implementation of these various instruments is still up to the national parliaments to decide. Thus far, there has been much disagreement on the matter. Some EU countries have already implemented a financial tax or a digital tax, while many continue to oppose them. Member states have consistently refused to relinquish their sovereignty in taxation matters and German Chancellor Angela Merkel is careful to emphasize that the measures are “exceptional.” The negotiations could be very long and, for this reason alone, a so-called national European federal state is still remote.

Centripetal forces

The emergence of European taxes would inevitably lead to the creation of a European tax administration. The European Parliament has already deemed the July agreement insufficient, given the financial slack promised to some member states. The body thus expressed a preference for more of the centralization so characteristic of the Brussel’s policymakers and bureaucracy.

The expansion of the EU budget is also a godsend for many lobbies and their experts, particularly clean energy and climate action.

Also, academics lean increasingly toward centralization. Of course, the existence of a common currency without a joint budget to absorb regional shocks has stood from the beginning in violation of what the economists consider an important condition of an optimal currency zone. These days, however, even Modern Monetary Theory comes to the rescue. Given very low borrowing rates (thanks to the expansionary monetary policy), many want to expand debt-financed fiscal policy at the national and European levels.

The expansion of the EU budget is also a godsend for many lobbies and their experts, especially in the domains that the Commission wants to boost as strategic – particularly clean energy and climate action. Some sectors, such as cycling, have already started to promote their social utility and push for “fairness” in divvying up the bigger cake – meaning that they should receive a large slice.

Other people’s money

The budget growth is also handy for national politicians. Several were quick to “explain” that companies outside the EU – like GAFAM – would pay the new taxes. However, as an elementary microeconomic analysis shows, there is a difference between the tax’s fiscal and economic incidence. It all depends on the elasticities of supply and demand on a given market: the less elastic side ends up paying most of the tax. Demand, i.e. consumers, thus usually pay in the end a substantial part of “taxes on companies.” In this case, the providers of digital services would introduce a price hike in Europe to offset the European tax.

French President Emmanuel Macron even assured the French audience that the “money will come from Europe on our budget without our needing to finance it, neither by our own debt nor by our taxes,” and further that “it is not the French taxpayer who will pay” for the stimulus plan. According to the French leader, there is such a thing as a free lunch. Such blatant attempts at public deception do not bode well for government transparency and accountability in the future.

Moreover, while praising European solidarity, Mr. Macron already perpetuates a division between “us” (France) and “them” (Europe). This will no doubt work as a shield for controversial French policies (think of the upcoming pension reform), but also is a guaranteed way to sow mistrust in the European community.

French schemes

The insistent French president was probably the main force behind Ms. Merkel’s reluctant reversal on the debt mutualization issue in May. The former had been pushing for that for quite some time. Politically, the deal helps toward several short-term goals of Mr. Macron. First and foremost, a breakup of the EU would have been problematic for France and other members.

Secondly, the French leader has presented himself as actively striving for a deal with Germany and Europe in the name of more “solidarity.” Given the decline of the president’s popularity in France, as a result of the Yellow Vests protests and various social tensions (especially among hospital workers), fixing his image problem before the 2022 election had become an urgent task.

As more numerous and still higher taxes kick in, the EU will feature more bureaucracy and fiscal illusion.

Thirdly, gaining access to additional money to spend before the election is not negligible for the incumbent. However, given that France stands to receive only about 40 billion euros from the recovery fund – an amount it could easily have borrowed or, better, saved by slashing public spending — one might wonder if the stimulus project actually does make sense from the French perspective.

But there is another way of looking at it, from the perspective of Paris. The growing EU budget means that, in the long term, Europe will acquire more and more of a “French spirit” in its governance. Brexit removed a powerful “frugal,” anti-Paris and anti-Brussels player. The Covid-19 crisis proved a perfect storm to push the EU in the direction of a Europe à la française – beyond a mere monetary union and toward a fiscal union. President Macron heeded Winston Churchill’s tip, from the time when the great man labored to put together the United Nations: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

Scenarios

Statist Europe

A first possibility envisions a more “statist” Europe. Longer-term, as more numerous and still higher taxes kick in, the EU will feature more bureaucracy, complex redistribution schemes (thus more fiscal illusion), and less accountability. The recovery fund comes with “investment” plans and new types of regulations, expanding the scope of central planning in the European economy. There will be more lobbying and waste of societal resources. If a federated Union emerges from this setup, those Europeans who cherish freedom, free markets and democratic accountability will have plenty of reasons to feel frustrated.

Frugal resistance

But another scenario is possible, as well. The resistance was shown by the “Frugal Four” (Austria, Denmark, The Netherlands and Sweden) until nearly the end of the July negotiations, and by Germany until May, which suggests that a political basis might be created for a differently structured Union. The “frugal” countries do not define European solidarity as having the Union’s spendthrift binge systematically financed by the provident members. That is why the final deal emerged less generous than initially envisioned — 390 billion euros in grants vs. 500 billion euros in grants — and came with conditions attached. The Northern countries will contribute less (about 7.6 billion euros in total) to the common budget. The countries in Southern Europe will have to implement reforms that will be watched closely. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, who acted as the unofficial leader of the “frugal” group, could not sell his soul cheaply.

Another promising element is the July election of Ireland’s Paschal Donohoe to the helm of the Eurogroup. This informal but influential body brings together ministers from the eurozone countries to discuss matters related to the common currency. While in favor of taxing GAFAMs, Mr. Donohoe wants this taxation to be implemented at the OECD level, not the EU level.

Not opposed to stimulus plans (he has shepherded some at home), he has nonetheless been quite a “frugal” minister of the economy. On his watch, Ireland has had the first surplus budget since the 2008-2009 financial crash. He favors tax competition and low corporate taxes – dirty words for Paris. Plus, he was elected over the Spanish socialist candidate Nadia Calvino, an economist by trade who could be called “the voice of the spendthrift south.”

There is hope that the small, frugal Northern countries are gathering strength to resist those who demand more of “other people’s money” in the name of solidarity to avoid the pain of reforming things at home. A scenario of this small group gradually imposing its agenda could be good news for accountability and, in fact, economic growth. To what extent can such a bloc become a factor?

In the spring of 2020, given its incoming presidency, Germany had to focus on building unity for the recovery fund project. However, its frugal nature will not fade away, and Berlin can be expected to push for accountability regarding the grants-for-reform. It is not as if Germany has turned against its former core allies.

Another factor will be the ability of the frugal camp to supply the market of ideas (both media and academia) with precise analyses of the French model’s implication for the federalist path, and of its dangers for a sustainable cohesion of Europe. This means pushing for general safeguards, such as accountability or unmasking fiscal illusion, and producing specific evaluations of the uses made by member countries of the fund grants. A serious promotional strategy in various languages also would not hurt. Much of the borrowing and spending reflex so prevalent in Southern states comes from an immature democratic culture, nurtured by a lack of transparency, and a now-dominant Keynesianism in the market of economic ideas. Both can be challenged.